Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road, 1955), is arguably the most significant Indian film. Its concurrent poetic and realistic depiction of a rural Bengal village transformed Indian cinema. Together with its two sequels, Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956) and Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959)—the “Apu Trilogy”—it positions Ray as one of the remarkable filmmakers of our era. What is even more astonishing, though possibly less recognized, is the breadth of the work that ensued. Ray has examined modern India through more than 30 feature films, shorts, and documentaries. He has created enchanting stories that attract both children and adults, has ventured into satire and detective genres, and has demonstrated his expertise in period films.

Ray was born in Calcutta in 1921, in Bengal, to a family of creatives and thinkers. His father, Sukumar Ray, was a prominent literary personality, an Indian counterpart of Edward Lear whose whimsical poetry remains beloved by children even now. Ray’s initial encounter with cinema occurred in his childhood when he watched Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd. During his youth, he immersed himself in the works of Frank Capra, John Huston, Billy Wilder, William Wyler, and other legendary Hollywood filmmakers, along with European and Soviet cinema. He subsequently pursued fine arts at Santiniketan, the institution founded by the Nobel-winning poet Rabindranath Tagore, who was Ray’s primary creative and intellectual inspiration.

Ray, similar to Tagore prior to him, was part of Bengal’s advancing middle class, the bhadralok, which spearheaded the Bengal Renaissance during the 19th century. The bhadralok maintained a balanced and thoughtful appreciation for both contemporary Western concepts and Indian customs, while aiming to eliminate traditions that hinder modernization, such as the caste system and the oppression of women.

Ray also utilizes the sensibilities and issues of the refined contemporary culture that emerged during India’s nationalist struggle against British rule. He is part of the group of artists who matured during this time—peers such as Ritwick Ghatak and Mrinal Sen, who similarly created their debut films in the late ’50s. These filmmakers certainly did not create the serious Indian cinema (as opposed to the mainstream, escapist musical drama); V. Shantaram’s Duniya nu Mane (The Unexpected, 1937), K. A. Abbas’ Dharti ke Lal (Children of the Earth, 1946), and Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (Two Acres of Land, 1953) had all received significant critical acclaim during their respective eras. What sets Ray and his contemporaries apart from the previous generation is their focus on rebuilding a newly independent society.

We observe a similar emphasis in the awakening of the titular heroine of Charulata (The Lonely Wife, 1964), Ray’s unquestionable masterpiece, as well as Bimala, one of the three key characters in Ghare-Baize (The Home and the World, 1984). It also appears in the tale of the feudal noble confronted by the crude yet affluent newcomer in Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958), and of the jobless and resentful young men in Pratidwandi (The Adversary, 1970) and Jana Aranva (The Middleman, 1975). The depictions of the caste system in Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder, 1973) and Sadgati (Deliverance, 1981) also reflect elements of change.

Ray has displayed a clearheaded and sensible approach in telling this story. His commitment to his own esthetics has meant that his films are ignored by the bulk of India’s cinema-going public, which prefers the musical melodramas and mythological films churned out by the studios of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta. Quite early in his career, Ray reflected,

What then should the serious filmmaker do? Should he accept the situation and apply himself to the making of serious mythologicals and serious devotionals, keeping the popular ingredients and clothing them in the semblance of art? This is obviously a way out of the impasse, but it raises an important question: can a serious filmmaker, working in India, afford to shut his eyes to the reality around him, the reality that is so poignant, and so urgently in need of interpretation in terms of the cinema? I do not think so.

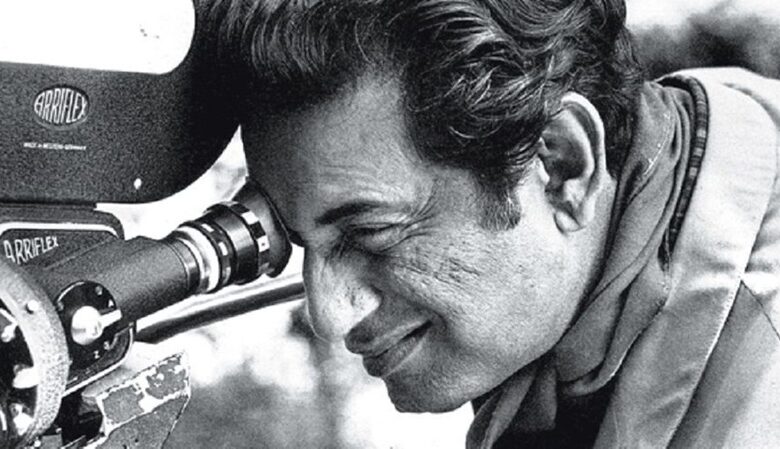

For Ray, catering to a minority audience has resulted in limited funds. This has resulted in significant outcomes. Following his viewing of Vittorio de Sica’s Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thief, 1948), Ray believed it provided a framework for his debut feature, and neo-Realist methods—profound use of settings, natural illumination—truly played a role in Pather Panchali. It has also been cost-effective for Ray to handle the camera personally, as he has since Charulata, editing on set and maintaining final film to footage ratios as low as 1:2 or 1:3. 3 However, Ray would be a thorough filmmaker without these thoughts. He not only directs but also pens his own scripts, many of which are original screenplays. Since Teen Kanya (Three Daughters, 1961, a three-part piece released in the U.S. minus one segment as Two Daughters), he has also created the music for his works. He possesses total authority over all elements of his movies and has left a personal mark on each of them.

Ray’s fascination with the individual and the nuanced nuances of character is clear in all his movies. Inner feelings, drives, and connections are shaped by a robust sense of visual and theatrical structure. Even a seemingly unstructured film such as Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forest, 1970) makes us sense that we understand the holidaying urbanites as unique personalities. We come to know Ashim, the polished executive, his friend Sanjoy, the cultured and empathetic Aparna, the athletic jock Hari, and the group’s humorist Sekhar. Through Ray’s nuanced and seamless interaction, the characters shape one another while also portraying themselves.

Ray stands out with a highly cinematic style, utilizing a powerful and articulate deployment of visual imagery to convey internal emotional states. In Charulata, the protagonist’s inner conflict is depicted through an intense closeup of actress Madhabi Mukherjee’s eyes gazing into the camera, subtly shifting in and out of focus as she sways gently on a swing. Landscapes also gain expressiveness, as seen in the opening scene of Distant Thunder, where the vibrant rice fields of Bengal mirror quickly shifting storm clouds and ultimately a blazing sunset in their shallow waters. The fields are lush; the impending hunger is caused by humans. Misfortune, grief, and demise threaten the future.

These are the qualities that have brought Ray’s films to a global audience. Naturally, there are restrictions. His “village” films have achieved greater success in the West compared to his “city” films, partially highlighting the allure of the exotic. His fascination with human connections and profound characterization frequently leads to films in which the rhythms and speech styles in the dialogue are vital—and impossible to translate. Similarly to any film, the enjoyment of his movies, which typically reveal through subtleties of human conduct, becomes more captivating with a deeper understanding of their cultural and artistic context. Probir’s discussions with his sister-in-law regarding his choice to leave his job in Shakha Proshakha (Branches of the Tree, 1990), for example, a movie featuring an elderly man observing the moral decline in his family, or the changes in relationships within an extended family in Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963), possess a realistic quality that is amplified by an understanding of the close yet formal dynamics present in an Indian family.

Ray’s assessment and acknowledgment of the issues facing modern India, along with his reluctance to suggest drastic remedies, have disappointed many, particularly within his homeland. There is a discomfort with political activism in his rejection of the focused radicalism of Siddhartha’s sibling Tunu in The Adversary. Likewise, the heroine of Seemahaddha (Company Limited, 1971) exhibits ambivalence toward her revolutionary boyfriend, facilitating her entry into her brother-in-law’s corporate realm—although she ultimately dismisses that realm due to its lack of ethics. Ray’s sympathies are with the contemplative person who has doubts and fluctuations instead of with revolutionaries asserting political certainties. In The Home and the World, he explores without reservation the psychological drivers behind Sandip, a leader of Swadeshi, a nationalist anti-British movement whose significant contribution to history is unquestionable by any contemporary Indian.

Ray is comfortable in his artistic inquiry and expression: “I think I like to present problems and make the public conscious of the presence of certain social problems and let them think for themselves. . . . I don’t think it’s necessary, important or right for an artist to provide answers, to say ‘this is right and this is wrong.’”4 His humanism goes beyond that of a liberal who does not agree with Marxist methods of social change; it represents the position of a modern mind that approaches India and the world at large through a commitment to the individual. In Shakha Proshakha, a bitter drama about the destruction of moral values and the corruption that swamps India today, one of the characters remarks on his confusion with the events in Eastern Europe and the crumbling of the Communist regimes. True to his approach, Ray explores problems by indicating how his characters experience them. At a time when countries are scrambling to cope with a globe spanned by the power of capitalism and consumerism, and intellectuals are faced with diminished ideological alternatives, his films stand in good stead. He may not have provided the answers, but he has asked crucial questions and retained for his characters their ultimate right—their humanity.